What is the Difference Between Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash? – Part 1: Origins and Scaling

Explore the Full Series of

“What is the Difference Between Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash?”

Part 1:

Origins and Scaling

What is the difference between Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash? This has been a topic of great interest for tech enthusiasts, business owners, and customers since the fork that separated the two cryptocurrencies. As the tech world advances and cryptocurrencies become more and more mainstream, it is important to comprehend how each digital currency works and which one may be more appropriate for your objectives.

In this blog post, we will explore the origins of both Bitcoin (BTC) and Bitcoin Cash (BCH), their evolution since their inception, as well as the scalability factors affecting them. We’ll compare SegWit vs an increased block size solution for transaction capacity along with transaction speeds and cost efficiency between BTC and BCH.

Get ready to delve into part one of a comprehensive analysis that uncovers the nuances distinguishing between Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash. By understanding these differences, you’ll gain valuable insights to help you navigate the intricate landscape of digital currencies and make informed decisions that align with your goals.

Table of Contents:

BCHFAQ Flipstarter - Phase 2

Join the Bitcoin Cash Revolution: Fund More Informative Content on BCHFAQ

The Origins of Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash

Bitcoin (BTC) and Bitcoin Cash (BCH) share a common origin as they are both branches of the same original, unified blockchain. Created by the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin was launched in 2009 as the world’s first cryptocurrency powered by blockchain technology.

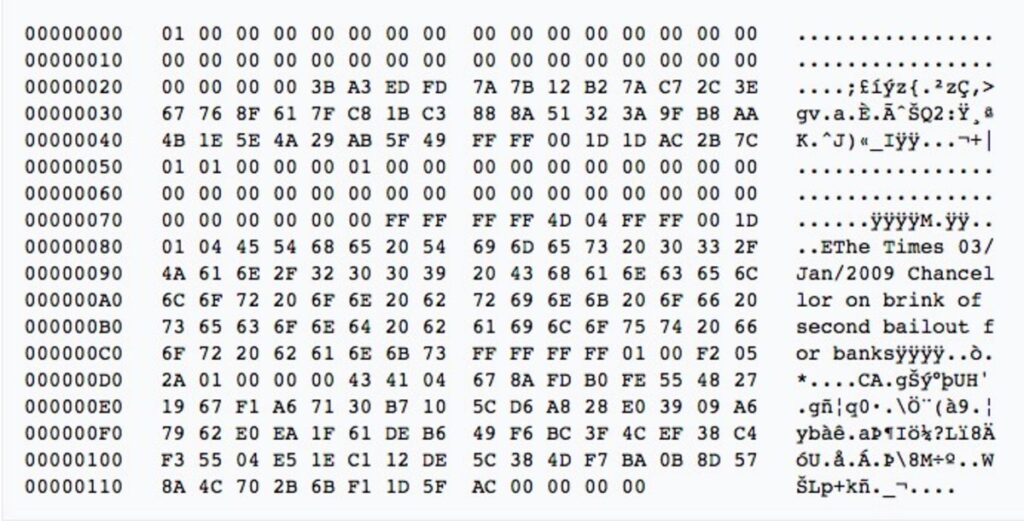

The very first block of the network (the genesis block) contained a message from Satoshi: “The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.” This message refers to the headline of an article in the London Times. While Satoshi never publicly commented on this message, many believe it essentially functions as a mission statement for Bitcoin as a new, decentralized tool that, if used, can prevent the many financial problems caused by central banking and government meddling.

Bitcoin became recognized as an extremely novel and disruptive financial tool. For the first time, value could be sent between people electronically without any middleman or central control. It was the dawn of a new age of money, with the potential to transform the entire financial landscape. On a more personal level, Bitcoin gave individuals an important tool to free themselves from economic censorship. For several years the community was unified on this singular glorious vision of global and personal monetary revolution. But the unity was not to last for long.

The seed for the eventual split between Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash was planted early on in the network’s history. In 2010, before Bitcoin had any recognized price, it was technically possible for network nodes to generate extremely large blocks of transactions for little or no cost that could potentially cripple the network. To prevent this possibility from happening on the budding network, Satoshi implemented a temporary block size limit of one megabyte (MB) while fully intending to allow for increasingly bigger blocks as the network matured. However, Satoshi eventually left the project and efforts to increase the block size commensurate with the user base and infrastructure were continually delayed by a lack of developer consensus.

The Rise of Bitcoin and Its Limitations

Bitcoin gained a lot of traction among tech investors, entrepreneurs, and consumers due to its impressive price increases, decentralized nature, seemingly-limitless accessibility, and first-mover advantage. Novel Bitcoin-based products and use cases were being released with increasing regularity and even traditional financial institutions felt the need to comment on the new tech. But as Bitcoin’s popularity grew, so did concerns about scalability and network efficiency.

The Bitcoin network became more and more congested over time, with transactions taking longer and longer to process while transaction fees increased significantly. These challenges exposed the limitations of the early block size limit of 1 MB when it came to handling high volumes of transactions efficiently. And these challenges came at a critical time when Bitcoin was becoming more well-known in popular culture and many businesses were increasingly interested in adding it as a payment method.

The community as a whole had always been extremely hopeful that the block size could simply be raised when blocks started to become full. Few realized how contentious the idea of scaling Bitcoin could become.

Key Takeaway:

Bitcoin (BTC) and Bitcoin Cash (BCH) originated from the same unified Bitcoin blockchain. Satoshi Nakamoto’s creation of Bitcoin marked the advent of decentralized digital currency, aiming to disrupt traditional financial systems. While Bitcoin gained widespread recognition and adoption, its popularity highlighted scalability challenges. Transactions became slower and costlier due to congestion on the network, revealing the limitations of the 1 MB block size.

Proposed Solutions for Scaling Issues

As the congestion problem steadily grew, multiple solutions were offered; some substantial while others were more modest. The major scaling solutions that the Bitcoin community was considering were:

An Increased Block Size Limit: The main proposal that had been in circulation since Satoshi simply involved increasing the maximum allowable block size on the Bitcoin protocol directly – allowing more transactions per block. But when some developers began making real plans for implementation, some in the community worried a block size increase would make it more difficult for node operators to store the entire blockchain. Others pointed out that normal users do not need to run full nodes. Instead, as Bitcoin processed more and more transactions in larger blocks, an increasing amount of cryptocurrency-centric entities and businesses (with a vested interest in the health of the network) could run plenty of nodes. That way, users could just be users, as Satoshi initially intended.

Segregated Witness: An alternative solution proposed was Segregated Witness (SegWit). SegWit’s aim was two-fold: eliminate transaction malleability (a particular vulnerability that allowed transactions to be altered by third parties) and increase block capacity. It accomplished both by separating the signature data from the rest of the transaction data, combined with a recalculation of the block space and how it is used. SegWit effectively allows for a block size of up to around 1.8 MB. However, it is up to wallets and other services to opt in to make use of the available space. SegWit proponents were also pleased that it would lay the groundwork for the Lightning Network (discussed below). However, a major concern about SegWit was the added technical debt in the protocol, complicating all future development and possibly introducing bugs. Opponents of SegWit pointed out that a straightforward block size increase, combined with a different malleability fix, made much more sense.

The Lightning Network: A second-layer protocol called the Lightning Network built on top of Bitcoin was proposed. It would theoretically enable faster and cheaper transactions by facilitating off-chain payment channels between participants. Users would be able to make one base-layer transaction to start a channel and then use that channel indefinitely before finally settling. Proponents of the Lightning Network claimed that it eliminated the need for a block size increase. Those in favor of bigger blocks recognized many potential problems of throttling the Bitcoin protocol and relying exclusively on second-layer scaling. They pointed out that even the authors of the Lightning Network whitepaper recognized the need for a much larger block size for the base layer.

The Hard Fork Heard Round the World

Eventually two camps formed and fought what is now known as the “block size wars”. One camp desperately wanted to increase the block size to get on-chain scaling that would allow more users and businesses to interact directly on the base layer of the protocol. It included many users, business leaders, and miners. They viewed increasing the block size as critical for continued growth, fearing all the progress gained up to that point could stall.

The other camp included many key Bitcoin Core developers (including all who were on the payroll of Blockstream, the leader in Lightning Network solutions) along with forum leaders, moderators, and their followers. The argument they used was focused primarily on the importance of keeping the block size small so that more nodes could be maintained by average users with modest hardware.

The small block camp maintained that the big blockers were ignoring the dangers of centralization and accused any attempt to change the protocol as changing Bitcoin into something that was no longer Bitcoin. The big block camp pointed to the original promise of Bitcoin as a peer-to-peer currency that could only be fulfilled by on-chain scaling. The big block camp also complained that the popular forums were using censorship and moderation to artificially control the narrative, putting the big block arguments at a severe disadvantage.

Eventually there was a compromise proposed called SegWit2x that seemed to get a critical mass of support from among all the stakeholders. It promised to implement SegWit first and later increase the block size limit to 2 MB. Despite this, many in the big block camp did not want SegWit implemented (due to the technical debt it would add to the Bitcoin protocol) and did not trust the other side to actually increase the block size as they had promised (a suspicion that was later confirmed). They realized that the only way to guarantee significant on-chain scaling was to fork the Bitcoin protocol which would create an entirely separate blockchain which shared a history with Bitcoin up to the moment of the fork.

In August 2017, a group of developers and miners took the initiative to make such a fork a reality, thus creating two separate cryptocurrency networks, one retaining the name Bitcoin (BTC) and the other eventually being called Bitcoin Cash (BCH). Bitcoin Cash aimed at addressing scalability issues by removing the hard-coded block size limit from the consensus rules and initially implementing a client-configurable limit of 8 MB, allowing for more transactions per block and lower fees compared to BTC.

The two communities have been split ever since, with BTC trying to increase transaction capacity through second-layer innovations and Bitcoin Cash focused on engineering larger and larger block sizes, with additional optimizations and improvements, on the base layer.

Key Takeaway:

Bitcoin Cash (BCH) and Bitcoin (BTC) branched apart in August 2017 as a result of concerns about scalability and network efficiency with (BTC). The hard fork removed the block size limit from the consensus rules on BCH, allowing for more transactions per block and lower fees compared to BTC.

Scalability Solutions

The primary difference between BTC and Bitcoin Cash right after the fork was the block size. BTC retained a block size limit of 1 MB and implemented SegWit, while Bitcoin Cash removed the consensus limit entirely and opted for an initial client-configurable limit of 8 MB. Since the fork, both BTC and Bitcoin Cash have incorporated further optimizations. We will analyze the advantages and drawbacks for all the scaling solutions implemented on each chain.

“Scaling” on BTC

SegWit was a soft-fork upgrade that sought to address scalability issues within the BTC blockchain. Introduced in 2017 by the Bitcoin Core development team, it separates signature data from transactions themselves, recalculates how block space is used, and gives a block space discount to SegWit transactions. This increased the number of transactions that can fit into each block, allowing an effective block size of ~1.8 MB (assuming all SegWit-compatible transactions, which is not required).

However, even with the SegWit upgrade, transaction capacity on BTC hits a theoretical maximum of 12 transactions per second (unrealistically assuming all transactions are SegWit-compatible), but in practice maxes out at eight transactions per second. In periods of high activity, this means that transaction fees can be very high. During the last few major Bitcoin price increases, average transaction fees went as high as $50. More recently, even outside of large fluctuations in price or activity, it’s not at all unusual to see transaction fees of a few dollars or more. Unfortunately this makes Bitcoin transactions unfeasible for smaller-value transactions and is especially difficult for those in the developing world where earnings are far less than in the developed world.

The SegWit upgrade paved the way for the Lightning Network, which enables instant payments with theoretically minimal fees across participating nodes on top of the BTC blockchain. With a single on-chain transaction, users can open a Lightning channel with a peer and theoretically transact thousands of times off-chain before settling the channel using another on-chain transaction. One of the main ideas of the Lightning Network is that if enough users are connected through payment channels, a payment route can be found that will connect any two users. This system has been touted as the primary scaling solution for BTC for many years.

Unfortunately the design and implementation of the Lightning Network has encountered a number of problems. Those problems include the difficulty of routing payments through many nodes, a lack of liquidity, and complications in usability. While a network of Lightning channels can theoretically allow for payment routing, the constant changing state of the entire network increases the difficulty of finding a route exponentially. Additionally, without a large amount of liquidity, payments may not get routed as expected. Recent data show that there is less than 5,000 BTC locked up on the Lightning Network (less than 0.03% of the total supply). These problems contribute heavily to the lack of usability on the Lightning Network.

The most common solution to some of these problems is to create channels with large hubs that have relatively large amounts of liquidity, but are regulated financial entities. Many users even allow these Lightning nodes to create and manage channels for them, foregoing self custody. These hubs contribute to the increasing centralization on the Lightning Network, as more and more channels end up being connected to them. The major drawback of such a solution is the re-introduction of central authority, banking regulation, and custodial control into Bitcoin, a tool originally meant to reduce reliance on such centralized solutions.

The central, and possibly sole, benefit of BTC’s perpetual block size limit of 1 MB is the very predictable and relatively small size of the blockchain. In a world where internet connections of 100 Mbps and hard drives of several terabytes are commonplace, the propagation and storage of 1 MB blocks is not a problem for virtually any individual node operator and certainly imposes negligible costs on Bitcoin-based institutions and businesses.

Key Takeaway:

While SegWit was introduced as a protocol upgrade to enhance scalability within the Bitcoin (BTC) blockchain, it only moderately increased transaction capacity from around seven transactions per second to a maximum of 12 transactions per second. Despite the SegWit-related Lightning Network’s promise of low-cost, instant transactions off-chain, it has faced complications in terms of routing, liquidity, and centralization. The core benefit of Bitcoin’s 1 MB block size limit lies in the predictable and manageable blockchain size, although it’s important to note that this advantage must be weighed against the limitations it poses on transaction throughput and cost.

Scaling on Bitcoin Cash

The creation of Bitcoin Cash was driven by a group of Bitcoin enthusiasts who believed that increasing the maximum block size would provide a more straightforward solution to scaling problems faced by the original Bitcoin network. At the fork that separated BTC and Bitcoin Cash, the latter removed the block size limit entirely from the network consensus rules. Instead of a block size limit for the protocol, a client-configurable excessive block (EB) became the standard. At the time of the fork, the EB was set to at 8 MB. With its initial larger effective limit of 8 MB, Bitcoin Cash was able to facilitate much faster confirmation times on average and lower fees due to the increased throughput capacity.

In May of 2018 Bitcoin Cash implemented further upgrades, including an EB of 32 MB. Bitcoin Cash developers have gone through multiple rounds of stress-testing on the mainnet and experimentation on the testnet to research further increases in the block size. 256 MB and even 1 GB blocks have already been demonstrated. Additionally, scaling up to VISA levels of transaction throughput is theoretically feasible. The benefits of such a large block size are many:

Scalability: The increased block size limit allows Bitcoin Cash to process a significantly larger number of transactions per second compared to BTC (approximately 240 tps on BCH vs 7 tps on BTC). This scalability improvement enables Bitcoin Cash to handle more users and transactions without experiencing congestion and higher fees during peak periods. It also allows for faster confirmation times, which is crucial for real-world use cases.

Lower transaction fees: With Bitcoin Cash’s larger block sizes designed to be well above what’s required for typical usage, extremely low (sub-cent) transaction fees are almost guaranteed for the vast majority of users. Lower fees make Bitcoin Cash more attractive for everyday transactions, especially for microtransactions or small-value transfers, which may not be feasible on other networks with higher fees.

Enhanced user experience: Faster and cheaper transactions contribute to an improved user experience. Users can send and receive funds quickly without having to wait for extended periods or pay exorbitant fees. A smoother and more efficient user experience is essential for mass adoption and widespread use of cryptocurrency in everyday life.

More use cases: The increased capacity of the Bitcoin Cash network opens up opportunities for more diverse use cases. With larger block sizes, applications and services can be built on top of Bitcoin Cash that require high transaction throughput, such as micropayments, online gaming, supply chain tracking, and other scenarios where frequent, low-cost transactions are necessary. Even Lightning-style payment channels would be more feasible on Bitcoin Cash than other constricted chains. Consistently low fees also allow for experimentation and innovation, leading to novel use cases that would be impossible elsewhere.

Efficiency: Due to Bitcoin Cash’s much lower mining hashrate compared to BTC (due to the much lower price), Bitcoin Cash mining uses less electricity. But even if BTC and Bitcoin Cash ever had equal amounts of hashrate, the much larger blocks of Bitcoin Cash would result in more efficiency, using less electricity per transaction than Bitcoin.

Decentralization: By having a larger block size limit, Bitcoin Cash aims to include a very large user base, allowing everyone to participate. While the size of the Bitcoin Cash blockchain may eventually become too challenging for the average user to sustain a node, with such a potentially vast user base Bitcoin Cash will be able to maintain a highly-decentralized network with a broad base of participants, including miners, full node operators, businesses, developers, and all other stakeholders. A higher block size limit allows for the possibility of more participants to contribute to the network’s security and operation, making it less susceptible to centralization by a few dominant players.

Key Takeaway:

Bitcoin Cash was conceived as a continuation of Bitcoin that addresses scalability concerns. Bitcoin Cash finally removed the block size limit that Satoshi Nakamoto put in place years earlier as a temporary measure. By adopting larger block sizes, Bitcoin Cash can process more transactions per second, leading to faster confirmation times, lower fees, and an overall improved user experience. The substantial block size also opens doors to diverse use cases such as micropayments, online gaming, supply chain tracking, and innovative applications. This design promotes efficiency, decentralization, and broad participation; making Bitcoin Cash a network with potential for mass adoption and a range of practical applications.

Conclusion

As the technological landscape evolves and cryptocurrencies continue their journey toward mainstream adoption, understanding exactly what is the difference between Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash becomes increasingly crucial. This initial exploration of their origins and scaling solutions has unveiled some fundamental disparities that have arisen since the fork that split these two cryptocurrencies. Both share a common origin in the innovative work of Satoshi Nakamoto, yet their trajectories have diverged significantly, leading to unique approaches to scalability and transaction efficiency.

The journey of Bitcoin as a pioneer of decentralized digital currency has transformed value exchange and storage, though not without challenges like the block size wars. While SegWit and the Lightning Network may have shown promise on BTC, they faced implementation complexities, liquidity issues, and centralization concerns. BTC continues to be the target of frustration with regards to its transaction efficiency amid rising demand. Conversely, Bitcoin Cash’s emergence stemmed from the belief that scalability should be addressed directly by larger block sizes. Embracing this approach, Bitcoin Cash achieved higher transaction throughput, quicker confirmations, and lower fees, paving the way for diverse applications and enhanced user experiences. While larger blocks entail node participation considerations, Bitcoin Cash is committed to broad decentralization.

In the dynamic world of digital currencies, understanding the nuances between Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash empowers investors, entrepreneurs, and users to make informed decisions aligned with their objectives. The journey from their shared origin to their divergent paths highlights the complexity and potential of blockchain technology. As these cryptocurrencies continue to evolve and adapt, their stories offer insights into the broader trends shaping the future of finance and digital innovation.

Explore the Full Series of

“What is the Difference Between Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash?”

Part 1:

Origins and Scaling

Stay in the loop – subscribe to receive instant notifications on our latest blog posts, delivered straight to your inbox